| innig.netMusicIn the HandsRecording MethodRecording and Editing |

I record digitally, of course — passionate (and questionable) debates about the Lost Virtues of Analog aside, it's the only reasonable way to make an affordable home studio. And heck, I think it sounds pretty darned good.

The computer you use doesn’t matter much. The sound quality is determined entirely by your audio interface and your software, so it pretty much come down to what platform you prefer. (I use a MacBook Pro, and it's magnificent.)

To connect the mics to the computer, I use a Presonus Firepod (now called the FP10). It has worked reliably and consistently, and sounds great. If you're doing piano only, and don't need more than two inputs, you could go with a 2-channel device like the AudioBox instead.

Before the Firepod, I used an M-Audio USB Duo. The sound was acceptable (many of the recordings on this site were made with it), but was an unending headache parade. After that awful experience, I strongly recommend against buying anything from M-Audio.

I currently use PreSonus Studio One, and have been fairly happy with it. In the past, I've used Logic, Peak, and Soundtrack Pro. I'm not wildly enthusiastic about any of them. I write software for a living, and they all strike me as awkward and unpolished. They have unnecessarily complicated user interfaces and more than a few bugs. Using them just makes me long for Adobe Illustrator. I don't know much about Pro Tools, Digital Performer or Cubase, but they're all well-respected programs and I hear good things about them.

UI issues aside, these are all powerful programs and do produce very fine results, if you're willing to wrestle with them. There are also a number of free and cheap options such as Audacity, but last I checked, the commercial ones used audibly better algorithms for sample rate conversion, downsampling, and EQ. That right there is really the one good reason to pay a few hundred bucks for the "light" version of one of the big DAWs.

I record at 96 kHz, 24 bits. To my surprise, I really can hear the different between 96/24 and regular 44.1/16 CD quality. So I do this with two thoughts: (1) eventually, higher-quality audio may be available to listeners, and (2) in the meantime, mixing and mastering done at a higher precision will have fewer artifacts when I render to CD quality.

I'm extremely meticulous about placing the mics in exactly the same location every time I record. This means that, once I've found a position I like, there's no further fussing with positioning every time I sit down to a new session. If you're not careful about where you place the mics, and their position varies slightly every time, you're going to cause yourself a world of hurt when you get to the mixing!

The one thing I do have to adjust every time I record is the input level — some pieces are louder than others! I play through some of the louder sections of the piece I'm recording, watching the peak level. In the past, the advice was always "record as hot as you possibly can," but I think this advice is increasingly invalid for modern technology: new A/D interfaces have incredibly low noise floors, so 6dB of extra noise is still negligible — and if you're recording at 24 bits, you've still got plenty of resolution to work with if you have to add gain later. Recording hot doesn't have the big advantages it used to. It still has the same problem, however: even the smallest amount of digital clipping sounds awful and is nearly impossible to correct. I'd thus rather err on the side of being a bit too quiet: I give myself a bare minimum of 6dB of headroom.

Once I've set the level, I play a few repeated chords right in the middle of the piano, with the pedal down, and adjust the left and right channels to come out more or less equal. This adjustment is much easier to make before recording than it is while mixing: my recording technique creates a very wide stereo image, and with a full piece going all over the keyboard, it can be hard to tell which channel is really louder.

Then comes the music. Playing for a microphone often creates the same kind of nerves as playing for an audience. In both cases, I find music struggling at first to wrench myself away from listening with the outer ear ("What is the listener hearing? What will they think?"), and toward the inner ear that listens inside the music — but in both cases, the inner ear takes over as I warm up and gather momentum. The keys to a good recording session are all the obvious things: good practicing, a calm mind, a decent meal, good rest, open ears, patience....

If like me you're working in a home studio that didn't cost a hundred grand, you're going to get unwanted noise in your recording: hum and rumble, creaks and pops, airplanes, lawnmowers, maybe wolves….

These sounds are a never-ending battle. Of course I do all the sensible things to head off the problem: record at times of day when the neighborhood is quiet and there aren't too many planes landing, turn off the refrigerator, turn off the furnace, etc. (I actually cut all but one of the circuit breakers in the house when recording. That ensures that as many objects as possible with motors and EM interference are stone cold off.)

Unwanted crap still sneaks in. Since creating the audio examples at the end of this tutorial, I've started using iZotope RX2 to clean some of these up. It's an astonishingly powerful piece of software: by far the best denoiser I've encountered, and its spectral surgery can do wonders. It's one of those rare pieces of software that radically altered my sense of what's possible. Yes, I still throw away some takes that were poisoned by an airplane — but RX lets my home studio sound a lot more like a real studio.

However, I'll warn right now against going too far down the road of audio cleanup. You can get obsessed quickly, and the obsession doesn't always have a good musical payoff. Unless it's really loud, background noise usually isn't as a big a problem as bad mic placement, bad EQ, or (worst of all!) a bad performance. Once you have a recording you love and really want to release, then rush out and buy RX!

If I don't have a good single complete take, the first task after recording is editing. This isn't a problem for the improvisations, which I publish just as they happened, but can take quite quite a long time with compositions. Just selecting which takes to use is quite time-consuming, and then making the splices smooth can make this whole phase add up to hours of work.

An aside on the philosophy of splicing: I'm skeptical of classical recordings with hundreds of splices that are pieced together entirely in the studio — it works well when the studio is part of the compositional process, but when the purpose of such splicing is obsessively perfectionist correction of live playing, it is dangerous. It can lead to a clinically perfect but spiritless recording without the organic expressiveness that makes music magical. However, neither am I in the camp that decries splicing as some kind of hoodwink or moral failing; recordings are recordings, not live performances, and a musician's job is to work their medium's full potential to produce the best possible experience. So when I splice, I try to strike a balance between correcting really conspicuous mistakes that disturb the flow of the music, and preserving that flow in its natural form.

In short: splices are artistic decisions, and must be treated as an aspect of musical performance, not as cosmetic surgery. End of aside.

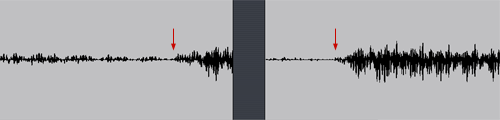

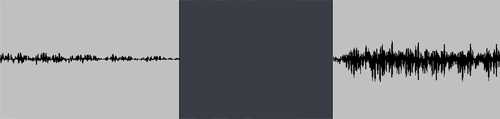

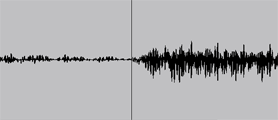

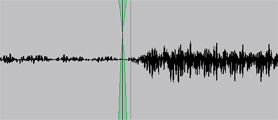

There are two essential criteria for a good splice:

It is easy to focus on one of these criteria at the expense of the other; keeping both in mind at once is difficult. The crossfade / edge blending features of modern editing programs help tremendously, but it's still a real trick. I find that the best crossfade time can be anywhere from 5ms to 2000ms; it's very much a case-by-case issue, and experimentation is key. Finding the right splice point is thus a matter of long trial and error.

Unless you have exceptionally good studio monitors, splicing is a job to do on headphones and then check on speakers. (I do splicing on a pair of Grados, which are surprisingly inexpensive for their quality.)

If you have reverb in your audio chain, turn it off when you splice. Reverb can mask problems.

I do the splicing in a multitrack editor, using multiple regions on the same track. Some approaches I often use:

A final warning on splicing pianos: the darned things have a lot of notes, and they reverberate like nobody's business. The transition from one note to the next is rarely as clear as our ears believe: the preceding notes ring into the next one a great deal.

We pianists are also far less consistent in tempo and dynamics than we believe — especially when starting in the middle of a passage. What we play depends on what we've been playing, and the sort of momentum we've built up.

For both these reasons, when you have a mistake you want to correct or a passage you want to redo, it works far better to start well in advance of the actually passage in question. Work your way into it; never start playing on the exact note you want to splice — even if it's easier to start there, even if it's the start of a new section, even if there's a rest before it. Back up and work your way in. You'll save yourself a bunch of heartache later!